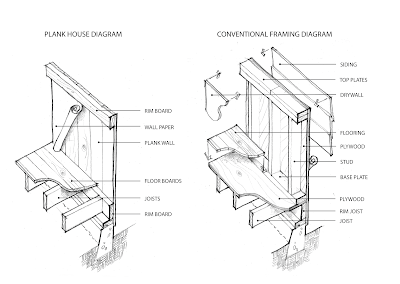

In fact one could argue a misplaced obsession with architectural permanence is exactly the cause of our present economic and environmental woes. Does every drink of water really deserve its own plastic bottle? To make things last only to use them in a disposable way is perhaps the most wasteful scenario one can imagine. A subtly more worthy and challenging goal is to strive for harmony and craft in our often speculative and impetuous cultural landscape. If one compares the way buildings are built now with the plank houses at Bodie one can see how things have "advanced". More parts have been introduced to address things discretely instead of embracing the economy of one element acting as something multi-functional (e.g. a board acting both structural and weather resistive).

When I tell my friends about the Bodie visit, most people have never heard of the place. The quarter million annual visitors are largely foreigners. It is easy to think of Bodie like an odd French obsession with Jerry Lewis or Marilyn Monroe; an affection that seems somehow misplaced and romantic. But this is too easy. Bodie is one of the few remaining monuments from our settler past and it has lessons to teach us about the virtues of a simpler approach. Many architects and carpenters muse about how things use to be built here. Go to Bodie and see. The simple plank house can be seen in all its rich and improvisational variety. There are over one hundred buildings.

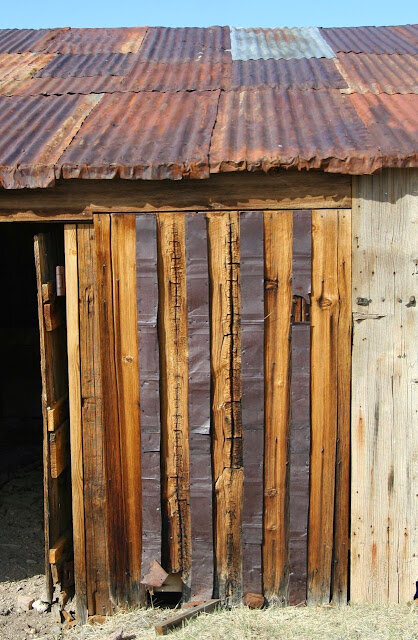

|

| Flattened sheet metal containers acting as battens |

Bodie is such a contrast to how europe memorializes its civilization. One can't help but wonder if it is only the distance from our existing civilization - so driven by our free market forces - that has spared this place the bulldozer.

About 70% of all US citizens live in megaregions. Despite the fact that at one time Bodie was one of the post prosperous gold mining towns in California, to visit it now is to venture off the beaten path. You can't see it from one of the interstates of our megaregions and it provokes the realization that the interstate itself has a kind of consistent atmosphere despite the specific place it might traverse.

When I was a child growing up in California it was a yearly ritual to visit the Sierras with my father and my sister for a week or two. A composer and musician, my father would would bring his violin with him on these trips. When I got older he'd have me bring my clarinet too and I have many memories of meeting people from all different parts of the US and elsewhere coming together around the campfire for singing and music making. While engaged in this "social camping", the last thing on our mind was to visit Bodie, despite its relative proximity. No one talked about it. We went to the Sierra's to get away from civilization and its discontents and Bodie, as a gold rush town, was a symbol of that legacy. Perhaps for that reason it wasn't a place we ever talked about going while we were hanging out in nature for a week or two.

My childhood home was San Leandro in the Bay Area. An area called "Okie hill" was tucked up alongside the freeway. This place was more recently known for having sporadic connections to the Hell's Angels, but its name went back to a time in California history when Oklahoma refugees landed there as a consequence of the dust bowl in the thirties.

My father really loved the dust bowl music of Woody Guthrie, the Oklahoma folk singer, and he was secretly proud of having taught his son, Arlo, music when Arlo was in high school back in Massachussetts.

When summer rolled around there in San Leandro we would head for the Sierras. The exodus to the Sierras is a little different than it is now. Many people aren't aware of the distinction that exists between national park and national forest land. Even today you can camp for free in many part of the national parks without much paperwork - especially if you're not camping in an "improved" campground. But most formal campgrounds today require a permit and often a visit to the mountains is preceded by an ironic stint spent in front of the computer making campground reservations.

Despite these "improvements" a few decades ago many of the summer campers were central valley citizens in between residences for the summer. Staying at a national forest campground was an inexpensive way for them to spend time with their kids in between school years without having to pay rent for a month or two. The camping was free and the streams were stocked with rainbow trout using tax money. Even though the time limit for a stay was two weeks, I remember more than once a family just picking up their stuff and moving to an adjacent camp site to "play nice" with the rules and avoid an annoyed ranger. It was a practical way to make quality time for your children on their summer break. I've always wondered if their might have been some kind of continuation of the itinerant Okie tradition in these loose networks of people that I hungout with for a few weeks each summer. So improvisational, so unpretentious and somehow so warm and human. Sharing fishing tips, marshmallows, matches and music; I've rarely felt closer to my fellow human being and nature all at once. Without exactly knowing why, surely there is something meaningful in the pursuit of a light environmental design that celebrates these two vital aspects of human existence simulatneously.